This is the eigth post of Mistakes Founders Make, a series of blog posts that shine light on legal mistakes that startups commonly make and attorneys have to fix. Keep in mind that the post sacrifices detail for simplicity and is for informational purposes only. It should not be taken as advice — whether legal, tax, or other — and does not create an attorney-client relationship.

This is the first part of a two-part mini-series on 83(b) elections. Here, we talk about why you, as the stock recipient, should make an 83(b) election. In the second part, we’ll talk about why your company should actually encourage stock recipients to make the election.

Just the basics

What’s the problem?

This is the eighth post of Mistakes Founders Make, a series of blog posts that shine light on legal mistakes that startups commonly make and attorneys have to fix. Keep in mind that the post sacrifices detail for simplicity and is for informational purposes only. It should not be taken as advice — whether legal, tax, or other — and does not create an attorney-client relationship.

How bad is it?

Bad. Very bad. Irreversible. The 30-day rule is a hard-and-fast one. You miss the deadline, you blow your chance to make the election.

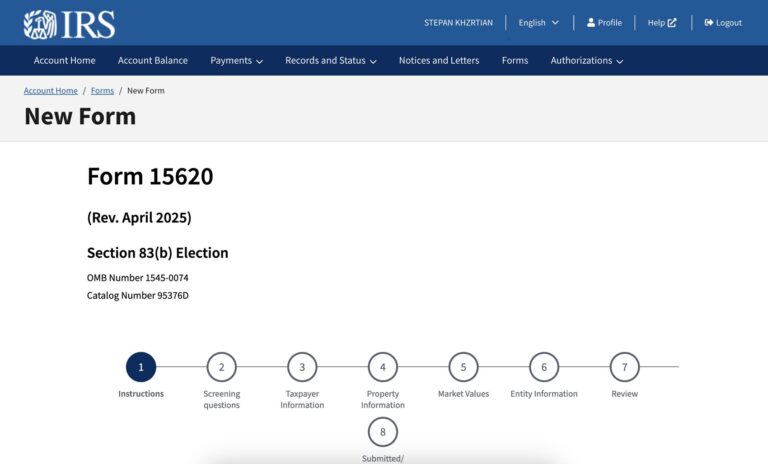

How do I avoid this?

Make the 83(b) election ASAP after you get restricted stock from your company. Your letter to the IRS should be postmarked no later than 30 days from the day your company gave you the restricted stock.

What’s an “83(b) election”?

In simple terms, an 83(b) election is a tax filing sent to the IRS telling them that you would like to pay any taxes due on your stock grant today rather than as the stock vests. You have 30 days to make this filing from the day your company gives you restricted stock.

Before we continue, I’d like to clarify two common confusions: (i) 83(b) elections are relevant only for equity that vests (it is irrelevant for equity that is fully vested upon grant); and (ii) 83(b) elections are irrelevant for stock options, even if they’re subject to vesting.

By “as the stock vests,” you mean like when stock is subject to 4-year vesting with a 1-year cliff?

Exactly. That’s an example of stock that’s subject to vesting, where 1/4th of the stock vests on the one-year anniversary of joining the company (this is the “cliff”) and, after that, the remainder vests monthly in equal 1/36th tranches over the next three years.

Ok, so what do taxes have to do with this?

You’re supposed to pay ordinary income tax on the difference of the value of the stock you’re getting minus the cash you paid for it. By default (as in when an 83(b) election is not made), the value of the stock is determined as of the date it vests, and the tax on that stock is paid when it vests. Let’s assume that the recipient is getting 48,000 shares subject to the vesting above.

- The recipient will not pay any tax upon joining the company, since no stock is vested at the time;

- The recipient will pay any tax due on 12,000 shares (or 1/4th of the stock) on the one-year anniversary of joining the company; and

- The recipient will pay any tax due on 1,000 shares (or 1/36th of the remaining stock) on each monthly anniversary after that.

Sounds like you delay paying taxes if you don’t make an 83(b) election. If so, then why would you make that election?

Excellent question. Here’s the catch: the value of the stock is likely going to go up over time. So 12,000 shares today is probably going to have less value than 12,000 shares a year from now; the same goes for the successive tranches of 1,000 shares. That extra value — the stock appreciation — is going to be factored into your tax liability if you don’t make an 83(b) election.

When you make an 83(b) election, sure, you have to pay tax earlier, but you’ll pay it on a lower value. In fact, if you pay the full value of the stock as of the date the company gives it to you, then your ordinary income tax liability will be zero.

You keep on stressing ordinary income tax. Seems like there’s something else as well.

Good catch, yes. Besides ordinary income tax, there’s also capital gains tax (I know, I know, hang in there). You’ll pay capital gains tax when you sell your stock later, on the difference between what you sell the stock for minus the value at which you got that stock. If you make an 83(b) election, that value is going to be less (as explained above), and so the capital gains tax is going to be more. So, while you’ll pay less in ordinary income tax, you’ll pay more in capital gains tax.

Now, this is a worthy trade-off, because generally, the ordinary income tax rate can be up to twice as much (up to 37% for 2022) as the capital gains tax rate (up to 20%). So, by making the election, you should be paying less tax on the stock appreciation value.

Anything else I should know?

When you make an 83(b) election, you pay any taxes due on all your stock, regardless if they eventually vest or not. So, if you leave the company before your stock fully vests and have to forfeit the unvested portion, you won’t be getting a refund for any tax you paid on that. That said, any taxes due in the 83(b) election scenario are likely to be small, if anything (especially in the early days), so this downside is manageable.