This is the fourth post of Mistakes Founders Make, a series of blog posts that shine light on legal mistakes that startups commonly make and attorneys have to fix. Keep in mind that the post sacrifices detail for simplicity and is for informational purposes only. It should not be taken as advice — whether legal, tax, or other — and does not create an attorney-client relationship.

Just the basics

What’s the problem?

You’ve signed an offer letter with a new hire committing to grant equity, but you delay formally approving the grant for whatever reason – oftentimes, because you’re waiting on a 409A valuation or you’re simply too busy with other tasks.

How bad is it?

Could get pretty bad. Exercise prices tend to go up over time, so delaying the grant could mean a higher cost to your employee — a “penalty” they’ll face for no fault of their own. Also, if an employee leaves your company before you grant their equity, you won’t be able to rely on your Stock Plan to do so. Further, you run the risk of exceeding your option pool by losing track of the options you’ve granted.

How do I avoid this?

Make granting equity a quarterly thing. Every quarter, the Board should approve all the equity that was promised to service providers over the past three months, and the service providers should receive and sign their equity grant documents.

What do you mean by “agreeing to give equity”?

It normally comes up when hiring a new employee. You give them an offer letter which talks about giving stock options or restricted stock, and they agree to it. It can also come up when hiring a consultant or an advisor and including equity compensation in the agreement. For simplicity, we’ll talk here about the main case: giving options to a new employee.

Isn’t signing that offer letter enough to give the equity?

Nope. The offer letter simply promises to give equity. It does not actually give it (or grant it, as lawyers say).

After the offer letter is accepted, you have a few more steps to take: your Board should approve the grant, your hire should sign the grant documents (mainly, a stock option agreement), and you should make a note on your cap table about having granted equity to that person.

Until these steps are completed – especially the first two – the equity is not considered granted. It’s merely a commitment, an unfulfilled promise.

So, what’s the problem?

Well, I’m glad you asked. There are quite a few hidden landmines in this situation, some of which are listed here.

Problem No. 1. Exercise prices tend to go up.

Options have an exercise price: the price that the recipient has to pay to buy the common stock. That exercise price is set when the Board grants the options and, as a general rule, should be equal to or more than the fair market value on the day the Board approves the grant. Normally, that exercise price is based on a 409A valuation report provided by an independent appraiser.

Exercise prices tend to go up over time. Say, you agreed to give equity to an employee you hired in 2019, when the company was just starting off and the fair market value of the stock was pretty low. Fast-forward several years, the company is gaining traction, and the fair market value of the stock has gone up perhaps by a multiple. Had you granted the equity back in 2019, your employee would have been in a much better position in regards to the exercise price of their options. But you didn’t, and now you can grant the options only at the current fair market value, potentially costing your employee a lot more money to exercise the options.

Problem No. 2. The employee leaves before the grant.

Sometimes, your employee leaves the company before the equity is actually granted. Well, here’s the thing: Equity Incentive Plans (also known as Stock Plans) make it super-easy to give equity to service providers (employees, consultants, and advisors)… but they cannot be used to give equity to people who aren’t providing services to your company. That includes ex-employees. This means that you can no longer use the options in the option pool to give equity to an ex-employee. In fact, you probably cannot give them options to begin with, and would have to consider giving restricted stock instead. If you do give restricted stock outside of the Plan, you’ll have a few hoops to jump through: does the company have enough authorized and unissued shares available? Do the preferred investors have to sign off on this grant? What federal and state securities exemption will you be relying on for this grant? The Stock Plan would have pre-empted all these questions.

Problem No. 3. Overgranting your option pool.

If you don’t grant the equity and update your cap table, you may quickly lose track of how many options you have left in your option pool. With that you run the risk of promising more options than you have the right to give. This can be fixed, but it requires a bunch of paperwork to do so.

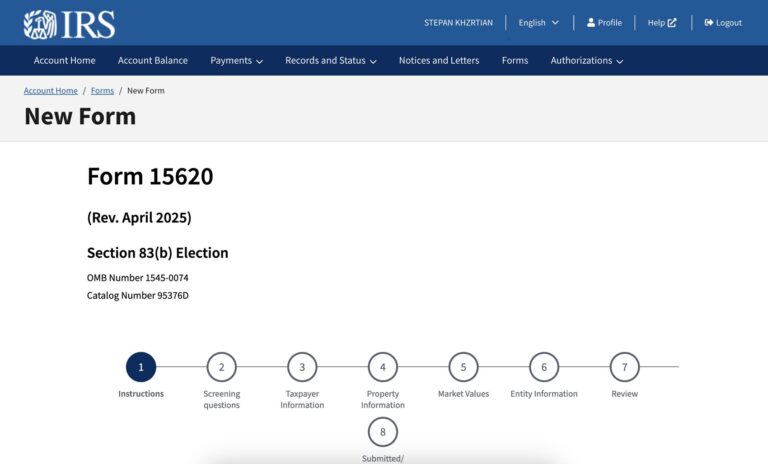

Can’t I go ahead and just backdate the Board consent?

A hard no on this one! Options live in the highly guarded intersection of the tax law realm and securities law realm, so unless you have an appetite for issues with the IRS and/or the SEC, it’s a hard pass on this.